NASA: Space Colonies & Starships

Technology and engineering discussion of possible space colonies designs. Space colonies, spaceships, design and technology for living in space, etc.

Technology and engineering discussion of possible space colonies designs. Space colonies, spaceships, design and technology for living in space, etc.Sources:

NASA and SSI of O'Neill Bernal Sphere design

NASA Stanford Torus design

NASA and SSI of Island Three paired cylinder design

A few illustrations - not the NASA ones

Starships and Space Colonies

Below are a few examples. You can click on images for a much larger version.

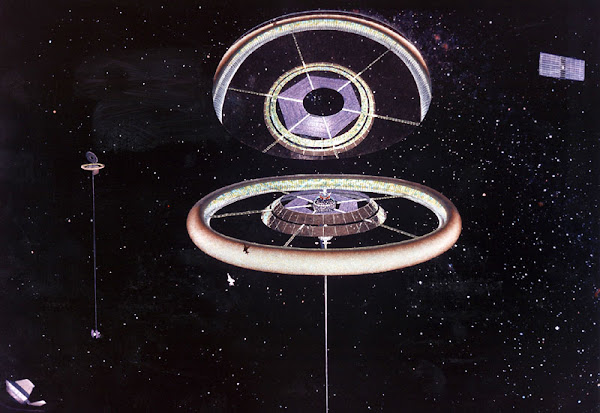

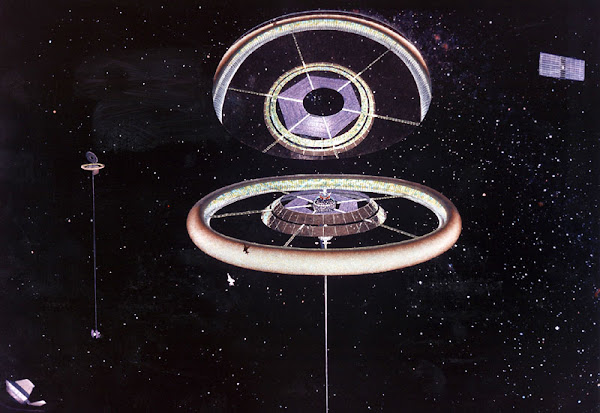

The Stanford Torus was the principal design considered by the 1975 NASA Summer Study, which was conducted in conjunction with Stanford University (and published as Space Settlements: A Design Study, NASA Publication SP-413). It consists of a torus or donut-shaped ring that is one mile in diameter, rotates once per minute to provide Earth-normal gravity on the inside of the outer ring, and which can house 10,000 people.

Stanford Torus external view. The overhead mirror brings sunlight into the colony through a series of louvred mirrors on the inner ring. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

Stanford Torus external view. The overhead mirror brings sunlight into the colony through a series of louvred mirrors on the inner ring. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

Stanford Torus cutaway view. The rotation of the torus provides Earth-normal gravity on the inside. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

Stanford Torus cutaway view. The rotation of the torus provides Earth-normal gravity on the inside. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

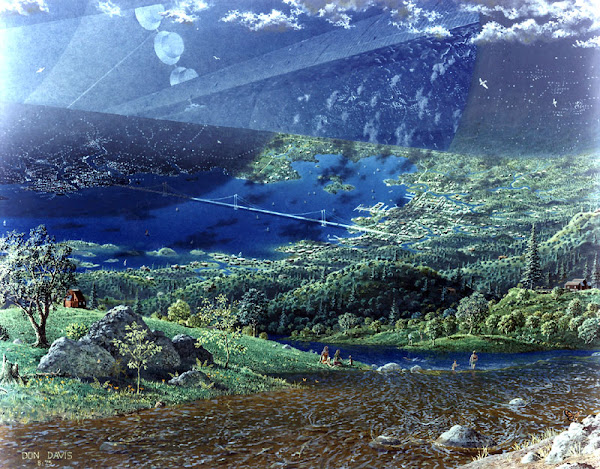

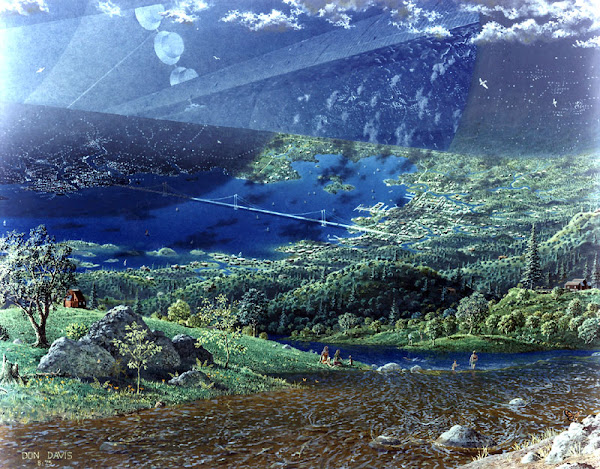

Stanford Torus interior. It seems unlikely that early colonies will have a population density this low. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

Stanford Torus interior. It seems unlikely that early colonies will have a population density this low. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

Stanford Torus agriculture, conducted on multiple tiers for efficient use of space. Agriculture in space can be very productive because of the controlled environment. Painting courtesy of NASA.

Stanford Torus agriculture, conducted on multiple tiers for efficient use of space. Agriculture in space can be very productive because of the controlled environment. Painting courtesy of NASA.

Stanford Torus construction. Depicted is the final stages of installation of the radiation shielding. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

Stanford Torus construction. Depicted is the final stages of installation of the radiation shielding. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

Source: Stanford Torus

The Bernal Sphere design is very similar to that used in the science fiction series Babylon 5, although the original Bernal Sphere design is much smaller, only 1 mile in circumference, and can house 10,000 people.

Bernal Sphere external view. It was later learned that the mirrors won't work properly in this configuration and will need to be redesigned. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

Bernal Sphere external view. It was later learned that the mirrors won't work properly in this configuration and will need to be redesigned. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

Bernal Sphere cutaway view. The sphere rotates twice per minute to provide Earth-normal gravity on the inside. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

Bernal Sphere cutaway view. The sphere rotates twice per minute to provide Earth-normal gravity on the inside. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

Bernal Sphere agricultural rings seen in cross-section. Farming occurs in the upper layers, and animal husbandry in the lower layers where gravity is a little stronger. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

Bernal Sphere agricultural rings seen in cross-section. Farming occurs in the upper layers, and animal husbandry in the lower layers where gravity is a little stronger. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

Bernal Sphere interior, complete with California-style wine and cheese party, and human powered flight in the lower-gravity area near the axis. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

Bernal Sphere interior, complete with California-style wine and cheese party, and human powered flight in the lower-gravity area near the axis. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

Bernal Sphere hub still in the construction phase, with shielding and mirrors being installed. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

Bernal Sphere hub still in the construction phase, with shielding and mirrors being installed. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

Bernal Sphere low-gravity recreation area at dusk, protected by netting. Gravity becomes lower as you approach the center, and at the very top are the zero-gravity honeymoon suites. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of L5 News and National Space Society.

Bernal Sphere low-gravity recreation area at dusk, protected by netting. Gravity becomes lower as you approach the center, and at the very top are the zero-gravity honeymoon suites. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of L5 News and National Space Society.

Source: Bernal Sphere

The O'Neill Cylinder, designed by Princeton physicist Gerard K. O'Neill, is considerably larger than the other two designs, and is referred to as an "Island 3" or 3rd-generation space colony. The configuration consists of a pair of cylinders, each 20 miles long and 4 miles in diameter. Each cylinder has three land areas alternating with three windows, and three mirrors that open and close to form a day-night cycle inside. The total land area inside a pair of cylinders is about 500 square miles and can house several million people. The cylinders are always in pairs which rotate in opposite directions, cancelling out any gyroscopic effect that would otherwise make it difficult to keep them aimed toward the sun.

O'Neill Cylinder exterior. The modules on the large ring structure around the endcap are used for agriculture. Each module could have differing environments ideal for a particular set of food items. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

O'Neill Cylinder exterior. The modules on the large ring structure around the endcap are used for agriculture. Each module could have differing environments ideal for a particular set of food items. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

O'Neill Cylinder interior provides a 20-mile vista. Children born here would think it totally normal to have "upside down" land areas overhead. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

O'Neill Cylinder interior provides a 20-mile vista. Children born here would think it totally normal to have "upside down" land areas overhead. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

A dramatic side view of an O'Neill Cylinder showing a cloud level forming at an altitude of 3000 feet. Painting copyright by Don Davis courtesy of the artist.

A dramatic side view of an O'Neill Cylinder showing a cloud level forming at an altitude of 3000 feet. Painting copyright by Don Davis courtesy of the artist.

O'Neill Cylinder endcap. The artist's inspiration came after O'Neill suggested to him that the view of San Francisco and the Golden Gate Bridge from Sausalito would provide an excellent scale reference for a later model cylindrical colony. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

O'Neill Cylinder endcap. The artist's inspiration came after O'Neill suggested to him that the view of San Francisco and the Golden Gate Bridge from Sausalito would provide an excellent scale reference for a later model cylindrical colony. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

O'Neill Cylinder vista with ruddy hues caused by a fairly rare solar eclipse. The cylinders are large enough to have weather, which could even be made to change with the seasons, perhaps depending on a colonist vote. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

O'Neill Cylinder vista with ruddy hues caused by a fairly rare solar eclipse. The cylinders are large enough to have weather, which could even be made to change with the seasons, perhaps depending on a colonist vote. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

Source: O'Neill Cylinder

Stanford Torus

The Stanford Torus was the principal design considered by the 1975 NASA Summer Study, which was conducted in conjunction with Stanford University (and published as Space Settlements: A Design Study, NASA Publication SP-413). It consists of a torus or donut-shaped ring that is one mile in diameter, rotates once per minute to provide Earth-normal gravity on the inside of the outer ring, and which can house 10,000 people.

Stanford Torus external view. The overhead mirror brings sunlight into the colony through a series of louvred mirrors on the inner ring. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

Stanford Torus external view. The overhead mirror brings sunlight into the colony through a series of louvred mirrors on the inner ring. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA. Stanford Torus cutaway view. The rotation of the torus provides Earth-normal gravity on the inside. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

Stanford Torus cutaway view. The rotation of the torus provides Earth-normal gravity on the inside. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA. Stanford Torus interior. It seems unlikely that early colonies will have a population density this low. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

Stanford Torus interior. It seems unlikely that early colonies will have a population density this low. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA. Stanford Torus agriculture, conducted on multiple tiers for efficient use of space. Agriculture in space can be very productive because of the controlled environment. Painting courtesy of NASA.

Stanford Torus agriculture, conducted on multiple tiers for efficient use of space. Agriculture in space can be very productive because of the controlled environment. Painting courtesy of NASA. Stanford Torus construction. Depicted is the final stages of installation of the radiation shielding. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

Stanford Torus construction. Depicted is the final stages of installation of the radiation shielding. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.Source: Stanford Torus

Bernal Sphere

The Bernal Sphere design is very similar to that used in the science fiction series Babylon 5, although the original Bernal Sphere design is much smaller, only 1 mile in circumference, and can house 10,000 people.

Bernal Sphere external view. It was later learned that the mirrors won't work properly in this configuration and will need to be redesigned. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

Bernal Sphere external view. It was later learned that the mirrors won't work properly in this configuration and will need to be redesigned. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA. Bernal Sphere cutaway view. The sphere rotates twice per minute to provide Earth-normal gravity on the inside. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

Bernal Sphere cutaway view. The sphere rotates twice per minute to provide Earth-normal gravity on the inside. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA. Bernal Sphere agricultural rings seen in cross-section. Farming occurs in the upper layers, and animal husbandry in the lower layers where gravity is a little stronger. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

Bernal Sphere agricultural rings seen in cross-section. Farming occurs in the upper layers, and animal husbandry in the lower layers where gravity is a little stronger. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA. Bernal Sphere interior, complete with California-style wine and cheese party, and human powered flight in the lower-gravity area near the axis. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

Bernal Sphere interior, complete with California-style wine and cheese party, and human powered flight in the lower-gravity area near the axis. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA. Bernal Sphere hub still in the construction phase, with shielding and mirrors being installed. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

Bernal Sphere hub still in the construction phase, with shielding and mirrors being installed. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA. Bernal Sphere low-gravity recreation area at dusk, protected by netting. Gravity becomes lower as you approach the center, and at the very top are the zero-gravity honeymoon suites. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of L5 News and National Space Society.

Bernal Sphere low-gravity recreation area at dusk, protected by netting. Gravity becomes lower as you approach the center, and at the very top are the zero-gravity honeymoon suites. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of L5 News and National Space Society.Source: Bernal Sphere

O'Neill Cylinder

The O'Neill Cylinder, designed by Princeton physicist Gerard K. O'Neill, is considerably larger than the other two designs, and is referred to as an "Island 3" or 3rd-generation space colony. The configuration consists of a pair of cylinders, each 20 miles long and 4 miles in diameter. Each cylinder has three land areas alternating with three windows, and three mirrors that open and close to form a day-night cycle inside. The total land area inside a pair of cylinders is about 500 square miles and can house several million people. The cylinders are always in pairs which rotate in opposite directions, cancelling out any gyroscopic effect that would otherwise make it difficult to keep them aimed toward the sun.

O'Neill Cylinder exterior. The modules on the large ring structure around the endcap are used for agriculture. Each module could have differing environments ideal for a particular set of food items. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

O'Neill Cylinder exterior. The modules on the large ring structure around the endcap are used for agriculture. Each module could have differing environments ideal for a particular set of food items. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA. O'Neill Cylinder interior provides a 20-mile vista. Children born here would think it totally normal to have "upside down" land areas overhead. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA.

O'Neill Cylinder interior provides a 20-mile vista. Children born here would think it totally normal to have "upside down" land areas overhead. Painting by Rick Guidice courtesy of NASA. A dramatic side view of an O'Neill Cylinder showing a cloud level forming at an altitude of 3000 feet. Painting copyright by Don Davis courtesy of the artist.

A dramatic side view of an O'Neill Cylinder showing a cloud level forming at an altitude of 3000 feet. Painting copyright by Don Davis courtesy of the artist. O'Neill Cylinder endcap. The artist's inspiration came after O'Neill suggested to him that the view of San Francisco and the Golden Gate Bridge from Sausalito would provide an excellent scale reference for a later model cylindrical colony. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

O'Neill Cylinder endcap. The artist's inspiration came after O'Neill suggested to him that the view of San Francisco and the Golden Gate Bridge from Sausalito would provide an excellent scale reference for a later model cylindrical colony. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA. O'Neill Cylinder vista with ruddy hues caused by a fairly rare solar eclipse. The cylinders are large enough to have weather, which could even be made to change with the seasons, perhaps depending on a colonist vote. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.

O'Neill Cylinder vista with ruddy hues caused by a fairly rare solar eclipse. The cylinders are large enough to have weather, which could even be made to change with the seasons, perhaps depending on a colonist vote. Painting by Don Davis courtesy of NASA.Source: O'Neill Cylinder

6 Comments:

the golden gate perspective made that piece of art even cooler.

I remember researching Gerard O'Neil's ideas on space colonies back in 1980 for my high school term paper. I had the pleasure of listening to him lecture at the University of Oklahoma. It's good to see his designs again and see how others have developed.

Oneill gravity: Seems to me that the only gravity one would experience in a rotating cylinder would be on the inner surface of the cylinder. So seeing clouds in illustrations of an Oneill cylinder seems wrong. While there would be some gravitational attraction between the surface and the water droplets in the cloud, it would be pretty limited. Have I got this wrong?

And the Dyson Sphere?

Not yet :)

tejasfalcon, you'd be dead right. I've been thinking about making an O'Neil cylinder colony the location of a story - L5-New Nanjing, of course - and that started to bother me.

I came up with the following:

There are three sources of energy, the "windows". Compared with them, the land is cold. Moisture's going to rise off the land, but the energy streaming in the "windows" is going to heat the air in the direct line of sight to the extent that it will constitute an enormous high, pushing the moist air back over the land again. However, inertia aka the coriolis force will mean that the moist air will spill over onto the "windows".

In other words, there will be massive fronts. That is where the clouds will form.

And rain? I suspect not a lot of it; but it will probably manifest itself as a mist or fog at night. And the reason it would land on the ground? The centre of the cylinder would be almost continuously full of hot air, mixing with cooler air rising. The moisture would either precipitate out onto the nearest solid objects or would superheat in the centre and increase the pressure even more, thus preventing any more moisture from entering that space; until nighttime, when it would cool and something closer to equilibrium would be established.

Post a Comment